The history of popular music is replete with stories of artists who chafed against the constraints of smalltown England and headed to America to seek their fortune on a bigger commercial stage. A rare example of someone traveling the other way is to be found in the story of Jimi Hendrix.

In a relatively short career leading up to his death in 1970 at the age of just 27, Hendrix proved himself as the most forward thinking guitarist of his generation, but his genius lay not just in redefining a single genre, but in smashing boundaries and blurring definitions. Drilled to perfection by countless hard hours of session work in the US with the likes of the Isley Brothers following an ill-starred stint in the army, he had the technical skills to rove freely between conventional rock music, the blues, psychedelia, jazz and something close to ambient music. His then-partner Kathy Etchingham has recalled him buying classical records and playing along with them in their shared flat in Mayfair.

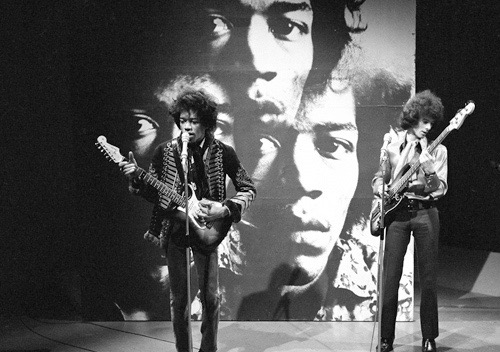

What Hendrix seemed to find in London wasn’t just a degree of relative domestic normality that had eluded him all his life back in the States, but a culture which was as open minded as he was. He stayed in the city for long periods throughout the last five years of his life, after making his first trip at the invitation of former Animals bassist Chas Chandler who had seen the young man play in New York and offered to manage him if he came to the UK. He made an impact from literally his first day, September 22nd, 1966: Mick Eve, saxophone player with Georgie Fame, recalled an excited Chandler collaring him on Denmark Street and demanding that he hear his new talent play. ‘I can hear him from here’, deadpanned the Cockney Eve, as Hendrix’s playing rang out across the road from the depths of a guitar shop.

The cultural current that Hendrix repeatedly stepped into in London was a complicated one running between the capital and the music of the US. At a time when much African American music was neglected and marginalised in its home country, a generation of musicians had rediscovered and reinterpreted it and were in the process of evolving it into something new. “Black American music got nowhere near white AM radio,” says the man who met Hendrix off his Pan Am flight at Heathrow, Tony Garland, who would manage Hendrix’s British company, Anim. “Here, there were a lot of white guys listening to blues from America and wanting to sound like their heroes.” Famously, when Eric Clapton first invited the unknown Hendrix on stage with him for a performance of Howlin’ Wolf’s Killing Floor at Regent Street Polytechnic, he subsequently groused to Chandler that ‘You never told me he was that good.’

When Hendrix moved with Etchingham into an apartment owned by Beatles drummer Ringo Starr at 34, Montagu Square in December 1966, he found himself surrounded by a kaleidoscope of creativity in all fields. “It’s a different kind of atmosphere here. People are more mild-mannered. I like all the little streets and the boutiques. It’s like a kind of fairyland,” Hendrix would later say of London. ‘I arrived here with just the suit I stood up in. I’m going back with the best wardrobe of gear that Carnaby Street can offer,’ he said. The fish-eye photo for the cover of debut album Are You Experienced? was taken in Kew Gardens in south west London. Musicians and managers gravitated towards The Ship pub on Wardour Street, conveniently close to the Marquee club and little changed to this day. Hendrix played everywhere from the Speakeasy and the Bag o’Nails to The Scotch of St James and the Royal Albert Hall, and shopped at One Stop Records on South Molton Street, where Elton John and Mick Jagger were also patrons. The only thing he didn’t seem enamoured with in London was the food: ‘English food, it’s difficult to explain,’ he told Melody Maker. ‘You get mashed potatoes with just about everything, and I ain’t gonna say anything good about that.’

Hendrix’s most significant base in London is the one that has enjoyed the longest afterlife: his flat at 23 Brook Street, Mayfair, which he shared with Etchingham and would describe as ‘the only home I ever had.’ By happy coincidence, the other half of the building at number 25 had been the home of George Frideric Handel from 1723 until his death in 1759. Hendrix knew of the building’s history and in a fitting tribute, the site is now a joint museum of the two men’s lives and work. Two visionary musicians both out of and ahead of their own time, both of whom left the country of their birth and found something in London that resonated with them, and allowed them to create in the way they wished, for the people who understood them.

Experience the historic culture of London for yourself in our Thirteen Bar which was created to celebrate the stories and culture brought by many rock stars over the years. After a night of history, drinks and fun, continue the party or call it a night in one of our Deluxe Apartments.

The Listening Bar, part three is now live 'London Haze'.

More journal entries to read

No. 21-25 Across Time

The whole of Denmark Street is steeped in creative history, but the parade from No. 21-25 has an especially rich heritage. Physically, this stretch of the street feels different from the rest of the street.

The Punk Era

Punk’s story evolved earlier from the margins both literally and geographically. In the west, 430 Kings Road hosted different incarnations of Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood’s boutique.